Essentials of Human Communication 8th Edition Chapter 2 Pdf

Chapter 2: Interpersonal Communication And Self

Introduction

A recent job search in Canada using the keyword "communication" yielded over 500 job openings. These jobs included those in customer service, business & IT, software development, legal services, healthcare, marketing, advertising, public relations, and engineering. In other words, virtually every type of job, in every level of an organization, employers value communication skills. Common phrases that reflected this valuation include detail oriented, good people skills, and customer-oriented attitude. In this chapter you will learn the evolution of interpersonal communication from its core principles developed in the 1950's to the way we develop self-identity in the age of the Internet. These principles provide the foundation for most of the applied communication theory and skills you will use in your personal and professional lives.

Practical Art & Theory

Interpersonal communication (IPC) skills can be learned, refined, and perfected. They are a "practical art." A practical art is one that has a specific function, is useful in multiple situations, and has local influences. By specific function it is meant that the IPC skill can result in, for example, a better job, a bigger sale, or more satisfying romantic relationship. It is also useful in multiple situations. For example, a person who is a good listener will communicate better both in their jobs and their personal relationships. By local influences it is meant that culture, social economic class, gender, religion, and other related influences help us to understand when it is appropriate to use certain IPC strategies and in what way. Even though a practical art has these influences, there are universal axioms that support all interpersonal communication. These axioms are based in research and are supported by solid theoretical concepts. In other words theory supports practice.

Theory is not a scary term. We theorize everyday about everything. Theory is just a specific way to think about something. It is a way in which we make sense of complex situations and helps us to make decisions. How often have you made a decision based on experience? Of course you have done this many times! In IPC we decide on the success and failure of friendships, romantic involvement, business and professional networking by theorizing. One student in a previous course like this wrote about how her past experiences with bullies influenced the way she developed friendships. She theorized that pushy people (her definition of a bully) did not make good close friends because every time she experienced power dynamics like these, the friendships did not endure. She used theory to understand her own strategies for interpersonal relationships and applied the practical art of interpersonal communication as a result. But what is interpersonal communication? Before we can understand the evolution of IPC we must define it.

IPC Defined

There are many good definitions of interpersonal communication.

Joseph DeVito (2007) defines it as a form of communication that takes place between two persons, who have an established relationship, and are in some way "connected" (p 5). This is what communication scholars refer to as a dyadic relationship. The word dyad is derived from Greek for two or "dyas." Psychologists use the term to describe (romantically linked) couples, but communication scholars expand this to refer to any two persons that have some sort of relationship – from friend to intimate partner. Dyads are dynamic. This means they change over time. Different contexts or situations will change the dyadic structure. For example, Bob and Mike are roommates and when they are together their friendship forms a dyad. John is an old friend of Bob's and does not know Mike very well. When John visits Bob and Mike, the dyad shifts from Bob and Mike to the primary relationship of the old friends John and Bob. Mike is no longer in the primary dyad. As the friendships change and develop this process may also shift and change. Therefore dyads are central to interpersonal relationships. This is an example of what is called dyadic primacy because, even if there are three people in the relationship, two of those three will have a primary relationship.

Purposes of IPC

The reason we study interpersonal communication is to learn about ourselves. In other words it helps us relate to others and to understand how our IPC influences these relationships. Interpersonal communication may be the largest of all the communication discipline specialties because the "self" is not static; it is what we refer to as dynamic. We are dynamic because we are always in a state of flux; changing for every context, relationship, and interaction. Have you ever heard someone say: "I'm not that person anymore." Or "I act so differently when I am at work." Or better yet, "Why does my father still treat me like a child?" These are statements that advance the notion of the dynamic self. In order to understand IPC we must begin by understanding ourselves.

Critical to discovering and examining "self" is the act of naming. When we are born our parents give us a name. These names often have meanings tied to them and reflect cultural ideologies and traditions. In my family, my parents followed a formula for naming their children. All the girls' names contained a variation of "Mary" (after my great- grandmother) and all the boys had a variation of "Edward" (after my father). My names, Teresa Mariann, were also my Catholic mother's favourite saints. As I grew older, I acquired the nickname "Tess" which I liked better than Teresa. I re-named myself to one that I felt suited my "real" self better. My experience is not unique in any sense, but it does exemplify the idea that the "self" is also a work in progress.

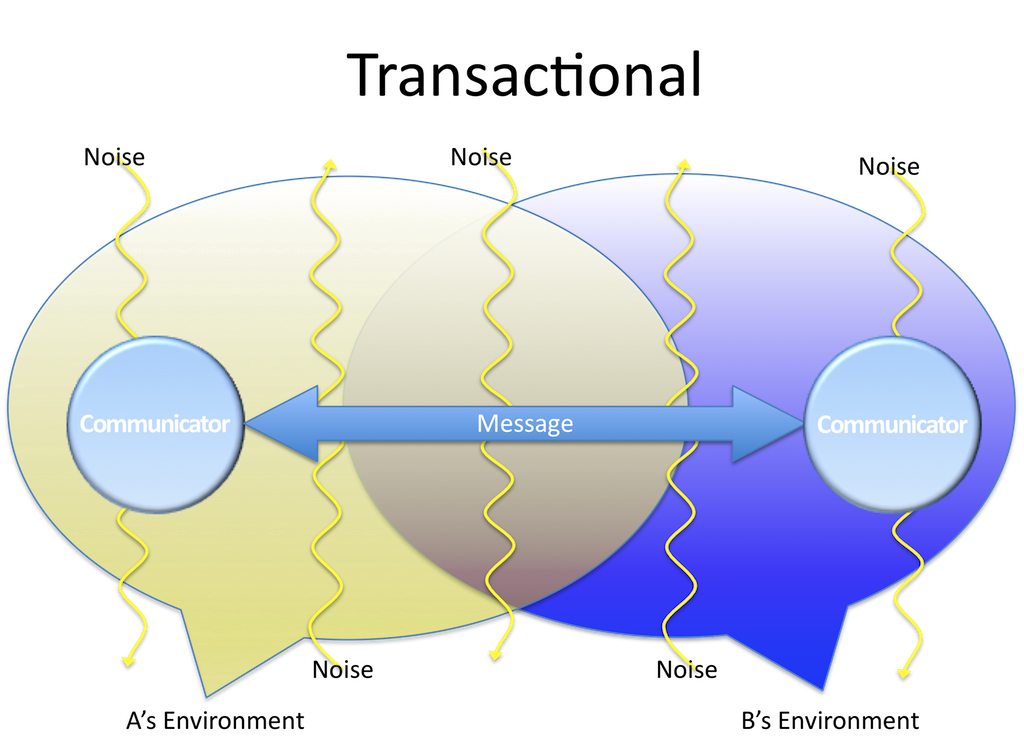

Naming is very important and this is also true in scholarly research. When Goffman (1959) wrote about "face work" fifty years ago, he named an important part of communication research- the face-to-face interpersonal interactions. As the field of communication expanded and became more complex, it became clear that there needed to be a set group of names all scholars would share. In 1996 Daena J. Goldsmith and Leslie Baxter published a "taxonomy" for speech events that occurred in interpersonal communication. In general, a "taxonomy" is a hierarchical way to categorize and classify groups of similar animals, plants, objects, or events. Goldsmith and Baxter (1996) are interpersonal scholars who specialize in relational communication and argued that taxonomy could also help catalogue experiences in social and personal relationships. They identified two major problems in the categories used by communication scholars from Goffman to the 1990's. First, they argued that previous research focused on the extraordinary events and behaviours and not the ordinary, mundane interactions of everyday life. Second, they claimed that previous research focused on the individual, and it was time to look at communication that occurred in relationships as "speech events." They defined a speech event as a "jointly enacted communication episode that is characterized by an internal coherence or unity & punctuated by clear beginning and ending boundaries" (p 88). In other words, these events occurred where people had established relationships and each type of event had a clear beginning and a clear end. They conducted a series of four quantitative studies that examined dyadic interactions and found that interpersonal communication in everyday life falls into six distinct categories. They also identified 29 distinct speech events and found that each one drew from common resources shared by the dyad, the closer the relationship the larger the repertoire of events, and these events were the building blocks of the dyad's reality. (See Sidebar 2.3.) This exemplifies the "transactional model" discussed in chapter one. Within this model there are eight constants or universal elements (DeVito, 2007).

Interpersonal Universals

As you recall from Chapter One, the transactional model of communication includes overlapping circles that represent the simultaneous communication flow in a dyad. The inner circle represents the general elements of influence, control, and directness. The middle circle concerns motivations for the interactions, and the outer circle represents the results that one hopes for within the interaction. (See Figure 2.1.) Within this model there are eight constants that influence the success of the communication. These are:

- Communicators

- Encoding-decoding

- Signals

- Channels

- Noise

- Contexts

- Ethics

- Competence

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1

The Transactional Model

First: The Communicators

Shannon and Weaver (1963), in their mathematical linear model of communication, referred to the communicators as the sender and the receiver. Claude Shannon was a researcher at Bell laboratories in the 1950's interested in improving the transmission of the spoken word over phone lines. Weaver took Shannon's model and applied it to interpersonal communication.

As you recall, in the Shannon-Weaver model the source formulates and sends messages, while the receiver perceives and comprehends messages. Each individual performs both roles. This is considered the foundation of dyadic communication. But there is much more to consider. Communication is not that "neat." I may receive your transmission, but I still need to understand what you said.

Second: Encoding-Decoding

In addition to sending and receiving we must encode and decode messages. Encoding is the act of producing messages. For example, I encode using gestures, spoken or written words. I write in English and I choose words that I believe my audience understands. These choices are based on how I was raised, my cultural background, my education, my experiences, my gender, and my socio-economic class. Decoding has the same influences. Decoding is understanding the messages.

Cindy Griffin (2009) defines encoding as "translating ideas and feelings into words, sounds and gestures" and decoding as "translating words, sounds, and gestures into ideas and feelings in an attempt to understand the message" (p 13). The key word in these definitions is "translate." Translating one person's ideas using our personal influences may result in a misunderstanding. How often have you said, "That's not what I meant!"?

Third: Signals

The third constant in this process is the message itself. Messages are the signals that serve as stimuli for the receiver. These can be auditory, visual tactile, olfactory, gustary, or any combination of all these. These may be intentional or unintentional. Intentional examples include things like gestures, accessories, clothes, your screen saver, the photos on a social networking site, or your avatar. Unintentional signals include things like a nervous twitch or a Freudian slip. (See Table 2.1)

SignalsAuditory (hearing)

Visual

Visual

Tactile (touch)

Olfactory (smell)

Gustary(taste)

Fourth: Channel

This is simply the medium by which the message is passed. For Shannon that was the telephone line. For Weaver this was the face-to-face (F2F) interaction. But the channel can be any combination or variation of: speak and listen (vocal/auditory channels), gesture/see (visual), or the emission of odours/smell (chemical/olfactory). These combinations can both restrict and bridge interpersonal communication. Depending on the channel, there may be some level of noise involved.

Fifth: Noise

Noise is anything that distorts or interferes with the communication of a message. There are four basic kinds of noise in IPC: physical, psychological, semantic, and physiological.

Physical noise is sometimes called external noise. (For example a lawn mower cutting grass outside a window.) But it can be any physical distortion like line interference on a phone, inability to read someone's handwriting, or the over crowded content of a network news web site. Internal or psychological noise comes from within the communicators. This could include pre-conceived notions about the other person (cultural differences), thinking about lunch because you missed breakfast, or the inability to concentrate because of a headache. Semantic noise is also internal because each person develops different meanings for even the simplest words. For example, a chair is a chair is a chair. It is a piece of furniture we sit on. But what comes to your mind when you think of "chair?" I can safely say that it is not the same image I have in my mind. When I think of the word "chair," I envision the blue rocker in my office. The definition is internalized by, and specific to, each individual. It is noise that causes misunderstandings. The last type of noise is physiological. This is a physical barrier within the speaker or listener that interferes with the communication. This includes things like visual impairments, hearing loss, or memory problems. Noise can be one of these or any combination of them, and they are all influenced by the universal of context.

Sixth: Context

Context is the situation or place that influences the form and content of the message. The meaning of the message, or the message's original intent can change when taken out of context. (See Sidebar 2.6.)

Context can also be obvious or ignorable. Background music can provide a mood for a situation, but is often ignored. The music seems so natural you don't even realize it is there until it stops. There are many obvious contexts too, such as the way we speak at a rock concert is far different than the way we speak in a church. What are the differences between a conversation at a sporting event vs. one at a funeral home? You can see by these examples that context is very important. Context is more than a physical location. There are at least 4 dimensions to context: physical, temporal, socio-psychological, and cultural.

Physical context is the tangible environment – a physical space such as a hallway outside a classroom, a bedroom, or a dinner table. It can also refer to the temperature. The way we frame our conversation differs when we are too cold or too hot. What kind of examples can you think of for this? Finally a physical context can also be part of a media environment like the way you talk in a social networking site or with a text message. Temporal context refers to time. This could be the time of day, or a moment in history. Ever say, "I guess you had to be there," when relating a story or joke that someone did not understand? This is an example of a temporal context that changed the joke's meaning. The third context that plays a role in interpersonal communication is the socio-psychological. This could be your community status or familial roles, or society's norms or rules. Cultural dimensions of context will be discussed in detail later in the semester when we discuss intercultural communication, but basically this relates to a specific culture's ideologies, and customs, or religious beliefs. The universals axioms of interpersonal communication can make for a very muddy interaction. The last two we need to negotiate in our interactions are ethics and competence.

Seventh: Ethics

Ethics is the moral dimension of communication because all communication has consequences. These consequences may be intended or unintended but there always consequences for our IPC. Ethical communication is easy to talk about and hard to do. To communicate in an ethical context you must speak the truth, be open and honest in your communication, and support diversity and freedom of expression. How many of you have spread gossip, or talked behind someone's back? Have you ever laughed at someone's off-colour jokes even though they made you feel uncomfortable? Ethical communication is more than not laughing at the joke; it is speaking up and expressing your displeasure. The consequences of this action may result in you experiencing backlash and ridicule, but if you commit to a life of ethical communication you must be prepared for this. The American Ethical Union has an excellent guide to successful ethical communication. These are:

- Seek to "elicit the best" in communications and interactions with other group members.

- Listen when others speak.

- Speak non-judgmentally.

- Speak from your own experience and perspective, expressing your own thoughts, needs, and feelings.

- Seek to understand others (rather than to be "right" or "more ethical than thou").

- Avoid speaking for others, for example by characterizing what others have said without checking your understanding, or by universalizing your opinions, beliefs, values, and conclusions.

- Manage your own personal boundaries: share only what you are comfortable sharing.

- Respect the personal boundaries of others.

- Avoid interrupting and side conversations.

- Make sure that everyone has time to speak, that all members have relatively equal "air time" if they want it.

Every professional organization follows a "Code of Ethics" and one example in Canada is the Canadian Marketing Association. Do a search for the professional organization you relate to and compare notes on the similarities and differences.

Eighth: Competence

The final universal element to interpersonal communication is competence. This is the ability to communicate effectively. As competent communicators we adjust language and behaviour according to the context, the person with which we are interacting, and a host of other factors. In fact we consider all the universals to access each interaction. The better our competence the more we are perceived in a positive way. We are perceived to be more intelligent, empathetic, and trustworthy. Through out his career in "facework" studies,

Goffman evaluated competence in everyday interactions and found this to be a strong indicator of all of these perceptions. A search of a communication research database found that the word "competence, interpersonal communication, and trust" for example, yielded over 200,000 articles and books in fields that included areas such as conflict studies, mobile commerce, organizational communication, intercultural communication, and interpersonal communication. But how do we access our competence? Before we can make a personal assessment though, we need to understand the communication concept of the "Self."

The Self and Interpersonal Communication

Who are you? Who am I? How are we the same or different? What is this concept of "self?"

Academics love to define things. But how can one define "self?" I had a student from Japan ask me to do so. He was trying to write a paper about the differences between the Japanese "self" compared to the North American idea of "self." I told him that while everyone knows what it is; no one knows what it is. This is because "self" is multidimensional, unique to every person, and influenced by self-concept, self-awareness, & self-esteem. The 'self" is also not some stagnant thing; it is dynamic to reflect the changes in each person's life. How often have you said, "I am not the same person I was five years ago," or had someone you loved say to you, "You've changed."?

Three Influences

Self-concept

Self-concept is the image you have of who you are. This image comes from many sources including others images of you, social comparisons, cultural teachings, and your own interpretations and evaluations of all these areas. There are branches of communication-related research that deal just in this area. In gender and communication, for example,

Nancy Chodorow (1978) is a sociologist who examines how we form identity within the family unit. For Chodorow the social dynamics of mothering recreates mothers in girls and fathers in boys. In other words, early relationships are central to gendered self-concepts or identity. Children internalize the views of their family and naturalize their individual roles and these serve to create the self.

Self-awareness

According to Amazon.com, there are over 2000 self-help books published every year. These books claim to help us find "our true self" or "our inner child" or even how to "discover yourself through fear." What all of the books have in common is their goal to help us become more self-aware. Self-awareness is defined as your knowledge of yourself. A tool to assess your personal self-awareness is called the Johari Window.

Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham (1955) [Joseph + Harry = Johari] developed this exercise to study group dynamics in organizations. Their work, from the 1950's helped develop this tool. The Johari window is useful in evaluating the extent to which you know who you are. As you can see from Table 2.2, there are four panes in the window: open self, blind self, hidden self, and unknown self. The open self contains the information known to you and others. This could be all of your behaviours, attitudes, feelings, desires, motivations, and ideas. For example, in my Johari Window I could include things like my name, skin colour, or gender. This pane varies according to whom you are interacting and communicating. (My open self in a social networking site may be my avatar, or public profile information.) The pane that represents the blind self contains the information known to others, but not to you. This could include unconscious habits you have such as stroking a non-existent beard while thinking, or pulling your hair when nervous. They may also include repressed experiences. One example of this is someone who witnesses a crime but does not recall it. Your friends might know you witnessed the crime; but your mind has suppressed the memory for some reason.

The last two panes of the window are the hidden self and the unknown self. The hidden self is the information known only to you not to anyone else. These are your secrets about yourself. For example, you may never reveal parental abuse, or you might hide an alcohol or drug problem. Items in this window are often selectively disclosed as your comfort level in a relationship increases. This is different than the unknown self. The unknown self is all the information you and others do not know. How is this possible? The unknown self is inferred from a variety of sources, and revealed thru experiences, dreams, psychoanalysis, or hypnosis. For example, a smell might jolt a memory you never knew you had. Although the unknown self is not easily manipulated; it is important to know it does exist. Once revealed, it moves into one of the other panes of the window. As part of this course you will construct a Johari Window for yourself by completing the "Who am I?" questionnaire. The goal is to increase your open self and decrease your unknown self.

| Known by Self | Unknown by Self | |

| Known by Others | Open Self | Blind Self |

| Unknown by Others | Hidden Self | Unknown Self |

Table 2.2

Johari Window – Assessment of the Self

Self-esteem

"How much do you like yourself?" Self-esteem is all about the value you place on yourself, or your perceived self worth. Many of the self-help books are aimed at increasing self-esteem, especially in women. Gender, culture, family roles, and relationships of all types play huge roles in our self-esteem. It is hard work maintaining a positive self-esteem. Four constructive steps to increase your self-esteem are to confront your own self-destructive beliefs, seek out affirmation, seek out nourishing people, and to work on projects that will be successful.

Try confronting your self-destructive beliefs. Many of us set ourselves up to fail by trying to live up to unrealistic goals. When doing the "Who am I?" exercise one student in a previous class wrote: "I must always be strong." By making this statement he held himself up to an impossible standard. He did not allow himself to be frightened, scared, or weak in any way. When he experienced fear, or any type of "weakness" he felt like a failure and his self-esteem diminished. Once he confronted this belief, all he needed to do was to re-visualize the goal into a more positive one. He decided to change "I must always be strong" to "I strive to be a strong person." Changing it in this way gave him permission to accept and embrace his moments of "weakness" without resulting in his self-esteem taking a nosedive. Doing this he realized his unrealistic goals and devised strategies to eliminate them.

The second step to a healthier self-esteem is to seek affirmation, or replace negative messages with positive ones. For example in my weight loss meetings we are told to focus on our accomplishments, not on what we look like (or think we look like). Instead of saying "I am so fat I need to loose 20 pounds" we should change it to "I am proud of the way I look now that I am no longer 200#!" Doing this increases self-esteem and motivates you to continue to work towards your goal. Another way to increase self-esteem is to seek out nourishing people. Avoid those people that

DeVito (2007) refers to as the drivers and the blockers. Drivers push you into negative ("Come on one more drink won't hurt you!") and blockers set up obstacles that stop you from advancing ("You're getting too thin. Eat something!"). The road to positive self-esteem is filled with drivers and blockers. Knowing they exist helps us stay on course.

The last step to a more positive self-esteem is to work on projects that will result in success. This does NOT mean that we should avoid doing things that are hard or challenge us. (If we did this no one would ever finish university, write a good book, or become an Olympic athlete). But not everyone will write the "Great Canadian" novel or break a world record in swimming. But we can measure success in positive and realistic ways if we remember success is relative. One person's "failure" is often another's "success." (See Sidebar 2.8) Just because something is hard does not mean we should not try. The key is to set realistic goals that can help achieve success at every step of the process. I am inspired by the story of a woman I met while I was riding public transportation in Alabama. She was quite heavy (easily more than 100 pounds over weight). As we got to know each other she began to tell me her weight loss story. She had already lost 100 pounds! She said she did not set out to loose 200 #. That was simply too much to conceive. Instead she concentrated on working on small projects that would result in her goal of weight loss. When she was 300# she could barely walk 10 feet without stress. Her first goal was to walk to the end of her driveway and back. Once she accomplished this she walked to her mailbox on the road and back. With each small success she set another realistic goal. Each success increased her self-esteem. When I met her she was walking 1 mile each day. That was over three years ago. I imagine that today she is a fit and healthy grandmother perhaps running a 5K with her grandchildren!

These four steps are the basis for most of the self-help books in the bookstores. Keeping them in mind could save you a lot of money! However, as I said earlier, this is easy to talk about but hard to do. We need others to help us. This is why we examine the "self" when learning about interpersonal communication. A dyad is made up of two unique "selfs." Interpersonal communication is integral to healthy selves and relationships. Key to this connection is the last thing this chapter discusses – self-disclosure. Self-disclosure is revealing information about yourself, to others, that is normally hidden. There are rewards and dangers in self-disclosure

Rewards include increased self-knowledge and the ability to cope with difficult situations. It results in more effective communication that can lead to more meaningful & enduring relationships. This, in turn can lead to better physical, emotional, and psychological health.

There are dangers such as personal risks, relational risks, and professional risks involved. One example that you as university students are faced with every day is what to disclose on a social networking site. While it may be fun to post those funny photos of you doing risky behavior (like drinking) it may not be the best thing to disclose this side of you to a potential employer, Remember that communication is irreversible – no matter what the form. Once it is said, once it is posted, you may be able to "delete" the entry but you cannot completely "take it back." Therefore we must be careful. In some situations you'll want to resist self-disclosure. If you feel like you are being pushed into doing so be assertive and do only what is in your best interests.Interpersonal communication

Wrapping it Up

In this chapter we begin to see how interpersonal communication as a discipline has it roots in sociology, anthropology, and other social science. Interpersonal communication research comprises the largest body of research and ranges from

Goffman's (1959) focus on individuals' "facework" to Goldsmith & Baxter's (1996) work on taxonomy of the speech act within a relationship. It is the foundation for one of the newest branch of communication studies – computer-mediated communication. Interpersonal communication is consists of eight universal elements and is integral to building positive identities. Interpersonal communication is more than an exchange of information from a sender to a receiver. It is an ongoing dynamic process that results in healthy relationships. Recognizing that successful interpersonal communication is an essential part of these healthy relationships contributes to a positive self-image and helps us make better decisions about our personal and professional lives.

Glossary

Interpersonal communication: a form of communication that takes place between two persons, who have an established relationship, and are in some way "connected" (DeVito, 2007, p. 5)

Dyad: refers to any two persons that have some sort of relationship – from friend to intimate partner.

Johari Window: tool developed by Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham in the 1950s to evaluate group dynamics. It is now used to evaluate the self in interpersonal communication.

Practical art: is an interpersonal skill that has a specific function, is useful in multiple situations, and has local influences.

Self-awareness:your knowledge of yourself.

Self-concept: the collection of beliefs one holds about oneself.

Self-disclosure: revealing information about yourself, to others, that is normally hidden.

Self-esteem: the value you place on yourself, or your perceived self worth.

Taxonomy: a way to categorize and classify groups of similar animals, plants, objects, or events. For example, biologists classify plants and animals using a hierarchical taxonomy that follows the patterns of Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species.

Understanding This Chapter

- What were the six kinds of talk Goldsmith and Baxter identified in their 1996 article? This article is over 10 years old. What has changed in interpersonal relationships since this was published? Would you change their taxonomy? How and why?

- What is in a name? Who has the right to name something? Why is this important?

- Go to a news website such as CNN.com, or Al Jayzeera.com and compare the noise on the sites. What restricts meaning making? What enhances it? Now do the same but compare the online version to the television version (channel). What are the similarities and differences you can identify? Can you do this with all of the universals?

- Practicing ethical communication. Sidebar 2.9 provides an example of ethical communication from the Northern Virginia Ethical Society. Go online and find Canadian websites that provide similar guidelines. Are there any differences or similarities? Why?

- The Johari Window is a useful tool used by business professionals in all areas. Go online and find two or three different uses for the tool. Compare, contrast, and criticize each one.

References

Chodorow, N. J. (1978). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the socialization of gender . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

DeVito, J. (2007). The interpersonal communication book (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Goffman, E. (1959). Presentation of self in everyday life . New York: DoubleDay.

Goldsmith, D. J., & Baxter, L. A. (1996). Constituting relationships in talk: A taxonomy of speech events in social and personal relationships. Human Communication Studies, 23, 87-114.

Griffin, C. (2009, 2006). Invitation to public speaking (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Cendage.

Luft, J. & Ingham, H. (1955). The Johari Window: a graphic model for interpersonal relationships. University of California Western Training Lab.

Weaver, W., & Shannon, C. E. (1963). The mathematical theory of communication. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

About the Author

Dr. Pierce is an Associate Professor at Ontario Tech in the Communication and Digital Media Studies program. Pierce received her undergraduate degree in Speech Communication from Colorado State University and her Master's degree in Human Communication from the University of Denver. Her PhD is in Women's Studies from Clark University. Her research focuses on the way we use the Internet to advocate for social change. The primary focus of her dissertation research was on the gendered discourse and personal narratives of cyberactivist women, or cyberconduits. She examined women's weblogs from Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan to understand the role the Internet played in these women's everyday lives. Weblogs mirror the Internet's culture of self- disclosure and community, are designed for audiences, and provide a space for established voices to be heard while creating spaces for new voices. These new voices, or cyberconduits, are cyberfeminists who advocate for social justice on a local level, and act as knowledge conduits by using digital media and technology such as blogging to connect with activists on a global scale. As a communication scholar, Pierce focuses on the ways we integrate communication in our everyday lives and how these, in turn, globalize our communication strategies. She has published in the areas of communication and the environment, and in the gendered politics of ICT. New interests include issues surrounding, STEM and the political rhetoric of science.

Essentials of Human Communication 8th Edition Chapter 2 Pdf

Source: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/evolutionhumancommunication/chapter/chapter-2/